|

|

|

Lost in regional strife, will nomadic Turkana be forgotten in Kenya? Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com February 4, 2008 The Turkana people of northern Kenya, thrown into prominence by the war in neighboring Sudan, may be in danger of being forgotten again. Turkana is a dusty, wind-swept province in northern Kenya, where scorching temperatures are only occasionally punctuated by short, but life-sustaining bursts of rain. More than 300,000 Turkana, a nomadic tribe, make their home here. For hundreds of years they've received little or no attention beyond sporadic interest from missionaries and anthropologists - it was only the horrors of war across the border that brought outside awareness of their plight. Now, with hostilities in South Sudan diminishing and the U.N. winding down operations for Sudanese refugees, the Turkana may be left to themselves again - but without anyone adequately addressing the changes in their lives brought by the war.

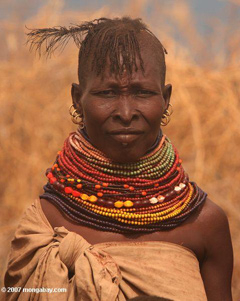

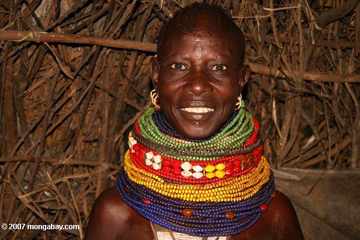

Lacking agriculture and savings accounts other than their livestock, the Turkana live on the brink of starvation. An extended dry season can destroy their sole source of wealth and nutrition, leaving children with bellies swollen from malnutrition, and the elderly and infirm withering away. Still, the Turkana are a proud people who are reluctant to give up their way of life. Part of this reluctance is a response to the harsh conditions of their environment, but some is because of misguided advice in the past from outsiders. While development experts have at times tried to persuade them to take up agriculture, the Turkana know that northern Kenya has too little rainfall to support most food crops. When rains do come, they can wreak havoc, causing rivers to overflow their banks, and wiping out fields, roads, and even unprepared communities. Elaborate fashion

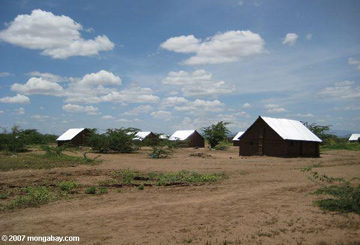

The Turkana build homes out of sticks, palm fronds, and animal skins, although today, around permanent settlements, the shelters are often weather-proofed with plastic tarps and discarded grain sacks from aid agencies. Handicrafts are fashioned from animal parts, and baskets are woven from sticks. Water - which women carry great distances from wells dug in dry stream beds - is typically transported in jerry cans instead of the traditional tanks made from animal parts. Between fetching water and herding livestock, the Turkana spend much of their day walking, and are commonly seen along roads, looking for rides on passing vehicles. KAKUMA The Kakuma refugee camp was set up in 1992 to accommodate 12,000 "lost boys and girls" of Sudan - unaccompanied children who first fled into Ethiopia to avoid fighting in Sudan. Many returned to Sudan, but then had to flee again, this time to northern Kenya. The camp grew quickly with refugees from the violence of Africa's Great Lake region, including Sudanese, Rwandans, Burundis, Somalis, Ethiopians, and Ugandans. At its peak in the early 2000s, the camp housed more than 100,000 refugees and was split into seven zones along roughly ethnic lines, divisions which remain today.

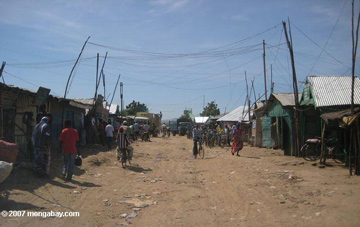

The Turkana have flocked to the camp because of its services and opportunities for trade. According to the U.N. High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), there were roughly 7,000 Turkana living around Kakuma when it was established in 1992; today there may be 40,000 who increasingly rely on the camp for commerce. Still, there is uneasiness between the refugees and the Turkana. The Turkana have difficulty understanding why aid agencies distribute food, health care, and education to refugees while they live in abject poverty and at the mercy of rainfall in a marginal environment. This, coupled with limitations imposed on both groups by UNHCR, has bred resentment and conflict between the two groups: in 2003 more than a dozen were killed in clashes. Nevertheless, there is a symbiotic relationship between the groups. Refugees - relatively cash-rich from remittances but resource poor - rely on the Turkana for charcoal, firewood, and water. In exchange, refugees pay the Turkana in currency which is used for buying foodstuffs and medicine for livestock. Still, the refugees are comparably better off, with access to health care and education, reliable food rations, and capital inflows to establish businesses - the camp even has a business district known as Little Mogadishu. In comparison, the Turkana have little idea of whether they will eat the next season, but they have freedom of movement and the right to own livestock - opportunities denied the refugees. AS THE U.N. MISSION WINDS DOWN, CHANGE IS IN THE WIND

As the U.N. pulls out of northern Kenya and aid groups shift operations into Juba and Rumbek in Sudan, some observers say that UNHCR will leave little more than 500 meters of tarmac road and scattered borehole water pumps. "Bill," a veteran development expert, notes that aid agencies focus on short-term fixes, and have missed opportunities to leave northern Kenya a better place for the Turkana. Instead of spending more than a million dollars a year for nearly two decades on gasoline for fuel generators, Bill says, development agencies could have invested in wind farms to exploit the region's strong and consistent breeze. The wind farms would have helped the Turkana make the transition from the disappearance of the camp and the departure of aid groups.

But despite resistance to new ideas, Turkana culture is changing. Family groups are now putting up permanent structures and no longer abandoning villages. But when they stop pursuing rainfall to more fertile areas, overgrazing and land disputes follow. At the same time, traditional practices are out of step with the changes occurring in the region. Fetching water from pits dugs in stream beds presents health risks in and around towns, and Turkana women now may be seen filling water containers from trash-strewn and oily puddles in the middle of dirt roads. Turkana who have reduced their reliance on herding now need to find other ways to make a living. In Lokichoggio, the last town before the so-called "No Man's Land" between Kenya and Tanzania, Turkana women wander the streets selling charcoal and sometimes themselves to buy flour and tobacco. Not all change is for the worse - indeed, a sedentary lifestyle brings advantages for the next generation of Turkana. As nomads, children were rarely schooled, but today they can attend schools set up by missionaries and even by the refugee camp - an estimated 10 percent of students in Kakuma are Turkana. Among some town-dwelling Turkana, there is optimism that cultural tourism could eventually draw visitors to the region, providing employment opportunities for locals as translators, guides, security guards, and staff in hotels. John Lokorio, of the Songot community near Lokichoggio, is working on establishing a tourism project with the nomadic Turkana of Nanam and Songot Mountain. He believes that by highlighting the culture of the Turkana and offering comfortable accommodations for travelers, the project could bring stable income to the community, even after the U.N. leaves. But efforts to launch the project have been difficult. Lokorio has won support from community elders but has failed to gain backing from an NGO, which the government says is needed to qualify for a grant.

Still, for all the aid brought to the region, little has trickled down to the Turkana. Schooling and training are helpful to the few Turkana who receive them, but most Turkana continue to live as they did in the past. With climate change expected to cause further drying and desertification in the region, the Turkana may be facing an ever more meager future. VISITING TURKANA

Arrangements can be made via the AFEX group, which can provide accommodations, transportation, security, and most importantly, local guides, translators, and friendly access to Turkana communities. AFEX runs a surprisingly deluxe operation in Lokichoggio, which still serves as a major jumping-off point for agencies working in Sudan. The camp, dubbed "Hotel California" houses employees from various NGOs and U.N. bodies, and offers high-speed Internet access, electricity, laundry services, and excellent food. AFEX can also make arrangements for visiting the Kakuma refugee camp. Safety: The U.S. State Department advises travelers against visiting this part of Kenya because of ongoing civil strife and banditry. AFEX can advise visitors on specific risks as well as offer advice on minimizing danger. News index | RSS | News Feed |

|